Lanna Atlas / History and Culture/ Mekong Tai peoples

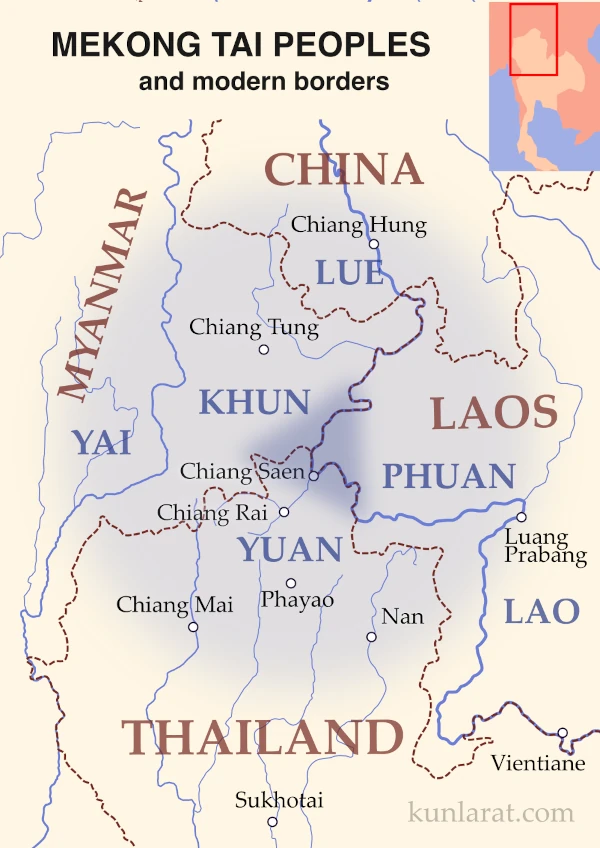

The flat valleys in the mountainous area in the north of Thailand, that once was the Kingdom of Lanna, are mainly inhabited by the kindred peoples belonging to greater Tai linguistic family – namely Tai Yuan, Tai Lue, Tai Yai, Tai Khun, Lao… and some others, smaller.

The historical homeland of all Tais is located somewhere in South China, and at the early stage of the history they had been somehow influenced by (ancient) China. Under pressure from the Chinese, many Tais gradually moved along the major rivers into mainland Southeast Asia and founded their polities-muangs on the fringes of the Indianized Mon and Khmer kingdoms. Nonetheless, ethnically Tais are entirely different either from Chinese, Burmese, or Khmers.

Part of the Tais migrated further down the Chao Phraya River plain, intermingled with the Khmers and other ancient peoples, received from them Hinduism and then Buddhism, and ultimately established the Kingdom of Siam with the capital Bangkok, which later consolidated many Tai lands and has become the glorious Kingdom of Thailand.

Other Tais remained to live in the mountain valleys in the Middle Mekong region and were left out of the sphere of the Angkor civilization. Their most important city – and also the oldest properly Tai city in Thailand – was Tai Yuan’s Chiang Saen, which later became the first capital of the Lanna Kingdom. That’s why scholars refer to the ethnic groups mentioned above as “Chiang Saen Tais”. But we’ll just call them Mekong Tais so that no one would be envious.

Dhamma script

During the 14th century, most of the Tais adopted Theravada Buddhism, and their old traditional belief in a realm of spirits (phi) called Satsana Phi (“Religion of spirits”) intermixed with the Buddhist worldview. Since then, every Tai village in Thailand, Laos, and Burma has had Theravada wat (temple-monastery), in which the monks spread the Dhamma, the teachings of Buddhism, by using texts written in Pali, the canonical language of the Theravada tradition.

The adoption of Buddhism opened up a certain cultural gap between the ancestors of modern Central Thais, majorly influenced by the Angkor Empire, and the ones of the Mekong Thais, who absorbed much of the Mon civilization. The point is that they started to use different scripts and liturgical texts, which led over time to the discrepancies in the ritual practices and their written languages.

In the South, the Siamese writing system, later developed into the modern Thai alphabet, derived from the Old Khmer script. The Thai language contains many words borrowed from Pali and Sanskrit through Khmer means. In the North, the Lanna rulers introduced the Old Mon scripture and ancient liturgical language, borrowed from the Old Mon manuscripts. The script spread from Lanna to surrounding areas such as modern-day Laos, Isan, Shan State, and Sipsong Panna, and the Lao, Tai Lue, Tai Yai, and some other Tai peoples – but not Thai Lanna anymore – still use the versions of distinctive Tham (the Dhamma) alphabet, which looks like the Burmese script.

As the local form of Buddhist worship took shape, the Mekong Tais found themselves linked together by some religious and cultural identity. The youngsters had to be ordained to the Buddhist monasteries as novices for studying the Dhamma. Through these studies, they learned to read and write the Tham script, which allowed the Mekong Tais to preserve and exchange their native knowledge in the area from Chiang Hung to Vientiane.

Mandala polities

Theravada Buddhism also brought the Mandala Principle into Tai’s social set-up. Mandala (Monthon in Thai), meaning “Sacred Circle” in Sanskrit, provides a versatile model of the divine macrocosm – everything has a central point from which energy flows to the periphery, and then back again.

Due to this principle, the mandala polities (muangs) were not merely physical territories with fixed borders, but rather variable human circles with charismatic rulers, whose right to rule derived both from their superior personal karma and from possession of the symbols of sacral power housed in their palaces. In their turn, each noble, prince, or king could be on the mandala periphery of a more spiritually powerful godlike potentate, or even a few of them.

Thus, the most valuable resource in the world of Mandala states was not land itself, but the people who could grow rice, build temples, be warriors and learned monks. No one other than slave hunters was interested in remote mountainous areas inhabited by the stateless Hill tribes, practicing hunting and slash-and-burn agriculture. Such territories were considered to be no man’s land and the abode of evil spirits.

So long as the lowland muangs acknowledged the superiority of the mighty overlord, they were a part of his mandala. Control over the mandala diminished as the overlord power, radiating from a center, got weaker – or, on the contrary, as the tributaries got stronger. If the seat of sacral power completely vanished, the mandala state disintegrated as well and its former political units sought either a different suzerain or full independence.

Four Mekong Tai Kingdoms

A fluid circles of power and influence were expanding and contracting in the Mekong valley for centures, often overlapped each other. Not once the whole region was dominated by the Lanna Kingdom. Northward from Lanna, the most durable overlord kingdoms in the Middle Mekong were Lane Xang, Keng Tung, and Sipsong Panna. Yet they themselves usually had vassal ties to China, Birma, or Siam.

The territory was finally divided by definite state borders in the form that had been shaped by the late 19th century. All four Mekong Tai subregions became part of the larger neighbouring countries: Lanna was included as part of Siam, later Thailand; Lan Xang first became part of the French colony of Indochina and then of Laos; Keng Tung was first colonized by Britain and then became part of Burma’s Shan state; Sipsong Panna was incorporated into the Chinese province of Yunnan.

These borders for a long time remained permeable, and later many Tais fled from wars and revolutions in their countries to the culturally similar territory of former Kingdom of Lanna. Now they make up a significant portion of the population of northern Thailand. But in general, Mekong Tai peoples living in different states evolved on their separate paths.

Tai and Thai… and Lao, Shan, Dai

Now it is time to define terms. The term “Tai” refers to the people in Thailand, Laos, China, Myanmar, and Vietnam who speak Tai languages and usually call themselves “Tai” relative to non-Tai people… with one big exception – the Laotians, who always replace in their country prefix “Tai” with “Lao” as a matter of national pride. For example, Tai Yuan and Tai Lue ethnic groups, living in Laos, are called there Lao Yuan and Lao Lue. It is said that the French colonialists taught Laotians this.

“Thai” with an “h” is linked only to the citizens of Thailand, which was formerly called Siam. In 1939, Siam’s government changed the name of the country to “Thailand” to help forge different Tai- and non-Thai-speaking peoples (Lao, Chinese, Khmers) into a single nation. A concerted “Thaification” program followed, spreading Standard Thai (Siamese) through schools and government, discouraging the use of the Lanna and Lao scripts, and inculcating reverence for the Thai monarchy. The process was largely successful, as the people of Thailand’s peripheral areas now entirely consider themselves members of the Thai nation.